12

Sep 11

Estimating Organic Search Opportunity: Part 2 of 2

In Part 1, we came up with a standard decay curve by position that can be used to estimate Click-Through Rate, provided you know how many clicks are available. In this posting we’ll extend that to provide two ways of estimating organic search traffic potential, complete with a downloadable spreadsheet. One approach is for keywords with no history, and the second one can be used for keywords with a history of performing, to project the effects of moving up various amounts.

Before we start, a number of commenters on Part 1 pointed out that the CTR decay curve will vary for individual keywords, your own performance will vary depending on how good your title, URL, and meta-descriptions are, and so on, some even going to the extent of asking why bother with this methodology at all?

For this I have two answers.

Pragmatic Answer

Yes, for an individual keyword, your mileage will indeed vary widely, but for hundreds or thousands of keywords, individual differences should “come out in the wash”. Of course, if your meta-descriptions are all terrible, your CTRs will all be terrible. But that’s what great about this methodology; if you are consistently getting low CTRs across ALL your keywords, you should take a close look at your overall strategy for writing titles,URLs, and meta-descriptions. If some pages are getting many fewer clicks than you would have expected, those are candidates for improving meta-descriptions, and so on.

Philosophical Answer

Why do people forecast, when the forecast is almost inevitably going to be wrong? When I was in the Semiconductor industry (which is notorious for being hard to forecast) I was heavily involved in the market research and forecasting community. I eventually came to sort of an existential crisis as a forecaster – I began to see that forecasting that market was so difficult, so why bother? So I asked a sage fellow named Jerry Hutcheson, “Why do people forecast at all?”, to which he gave this odd, but great reply:

“It’s primal. Sometimes people just want to take a look at the chicken entrails and see what they say”.

To apply this to SEO, I think what this means is: clients expect a forecast, you need at least some kind of ballpark to give you a sense of what’s achievable, so it’s inevitable you *will* forecast. We forecast because we must.

So, if we must forecast organic opportunity, let us at least try to do it as accurately as possible.

The Two Remaining Problems

In Part 1, we pointed out two problems with using these position vs. CTR curves; although Google’s Adwords Keyword Research tool gives you total search impressions, not all of them are available. Some go to paid search; and some are “abandoned searches” where there is NO CLICK.

How many clicks go to paid search?

Google recently did a study called Incremental Clicks Impact Of Search Advertising to demonstrate “how organic clicks change when search ads are present and when search ad campaigns are turned off”. I am highly skeptical of this study, because Google has a huge incentive to put out research that might lead one to the conclusion that one should spend money on search ads.

Reviewing the study, the key line that jumps right out of the study is:

“To make comparison across multiple studies easier, we express the incremental clicks as a percentage of the change in paid clicks.

By reporting *percentages* from the study only, they succeeded in avoiding exposing actual click numbers, from which one could infer Google’s actual “abandoned search” or “search success” rates.

Also, basing the reporting as a percentage of *paid clicks* strikes me as very odd, at the least; wouldn’t using organic clicks as the base value of comparison make more sense, if the purpose were to identify incremental clicks from sponsored search? This looks a bit like a redefinition of what the average person would likely think the term “incremental” in the title of the paper is supposed to imply, i.e. incremental over non-paid search.

Either way, this study is not useful to us for our purpose here (if for any at all perhaps ;-). I simply point it out to avoid getting comments and emails pointing it out.

We Can Use The CTR Curve Itself to Estimate Paid Search

While you will see numerous postings on the web talking about how 35% or 33% of clicks go to paid search, there’s little evidence to back those statements up. After doing some extensive research on this, I failed to come up with any really solid evidence I trust. I did find one credible and well documented study by Dogpile, the meta-search engine, in 2007 called Different Engines, Different Results, which found:

1,) 20-29% of first page search results are NOT sponsored (page 13)

2.) The percent of searches on Google that did *not* display sponsored results (presumably all page results) was (34.8% (page 15) + 22.8% (page 14)) = 57.6%.

Let’s assume the following:

A.) Google has probably improved the percentage of searches that display sponsored results since 2007 somewhat; let’s assume the number is 50%.

B.) Let’s assume that the sponsored search results get prime positioning over the organic results (not really an assumption a fact – often the top 3 results are paid search ABOVE organic). So those slots should have high CTRs; let’s assume we can apply a curve to them just like any other results.

Let’s use the curve we developed in Part 1 to see what a reasonable range would be for those CTRs.

If we assume the curve shifts up and applies just as well to the top of the page (in the case where we’re including sponsored results rather than excluding them), we would expect that if 3 sponsored results are all that are displayed, and all appear 100% of the time at the top, then they should garner (20% + 10.61% + 7.32%) = 37.93% of all clicks.

But since (let’s assume) 50% of searches do not display search ads, then perhaps the 50% of clicks paid search ads receive is half of that, or 18.96%.

Let’s therefore be a little conservative and round up and assume that 20% of all clicks go to paid search and 80% go to organic. If anyone has any ideas, data, thoughts, or opinions on this otherwise, by all means, comment below. It’s shocking to me that there are no clear, solid numbers in this industry available on this.

How many Searches are “abandoned”?

Unfortunately, the major sources of information on abandonment rates for search queries which are widely quoted around the web are two sources that I consider unreliable.

There are a number of studies by iProspect, where users were *asked* about their search behavior, but their search behavior was not actually *measured*. Surveys are a *terrible* way to try to get at this data, as users really have no idea how often they are actually clicking on the second page of search results, abandoning searches and so on. Thought experiment – do you know these numbers for your own behavior? I doubt it! You can Google the iProspect studies if of interest, but for our purposes I consider them unreliable.

The other source of note was some research put out earlier this year by Hitwise that measured Google’s “success rate” (the opposite of their abandonment rate). Matt Cutts debunked this in a short blog posting – probably because Google’s “failure rate” was shown to be worse than Bing’s. Notably however, Matt did not disclose what Google’s “failure rate” actually is. Very interesting.

It’s shocking to me that no one seems to have information on Google’s overall abandonment rate for searches. In fact, I have done an extensive search and have been unable to find anywhere where Google has EVER disclosed this. I am sure it’s a key metric internally at Google that is watched closely, and it appears to be a closely held secret; perhaps the abandonment rate is one of the levers that Google can push on when they are trying to “make their numbers”, or maybe it’s THE key competitive metric that Bing and Google are all about.

However, I was able to find two credible studies on this by a few Greek researchers:

Queries without Clicks: Successful or Failed Searches

Interpreting User Inactivity on Search Results (requires purchase)

The researchers took an interesting approach of asking test subjects about their queries (before the query), but also measuring the queries directly to determine whether they were successful or not (they even asked subjects why, after the fact). The two studies had slightly different results, but if you add them together, 1874 queries were analyzed, 377 of which were “abandoned”, which is roughly a 20% abandonment rate.

These studies have some flaws; the test subjects were all computer science graduate students – likely better searchers as they all understand Boolean logic, and one can argue that by asking users about their queries before they initiate them, they may be putting more thought into query construction than a typical user would.

So I believe this 20% number represents a floor, the true number you would find with the average searcher is likely higher; we’ll assume 30% for our purposes.

Put It All Together And It’s *Still* Too High

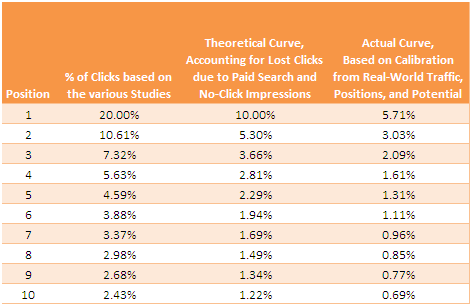

So, if 20% of search impressions go to paid search, and another 30% are “abandoned” searches, that means we simply have to cut our percentages in half. I did so using the second column in the following chart, and then applied that potential to 870 keywords for a website with known traffic and known positions. Note that I calibrated this with *broad match* values from the Adwords Keyword Research Tool, not exact match:

These were all non-brand keywords, with a fairly normal amount of universal search results mixed in. This website is very SEO-optimized, the meta-descriptions are great, and so on, so I think it’s representative of what a typical SEO project would aspire to. If you’re forecasting improvements for branded keywords, you’re not really doing your client much of a favor – they should rank for those anyway. The key improvements to target for any SEO project (other than branded keywords experiencing improved CTRs after initial meta-description hygiene and so on) are improvements to non-branded keywords (existing, and additional).

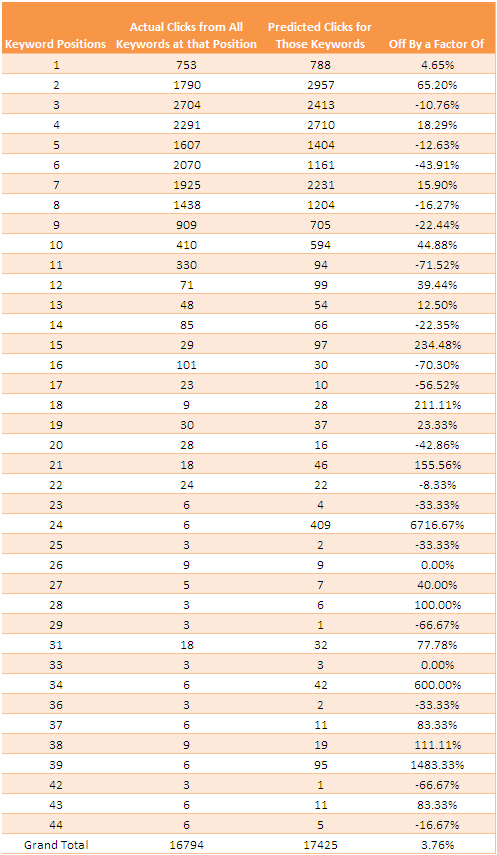

When I did this, the predicted traffic numbers had the following characteristics:

1.) They were *wildly* off for individual keywords – numbers like 95% to +3,000% – all over the map. In fact, it looked useless when I examined it this way.

2.) However, when I aggregated the keywords by position, the differences were much smaller. And overall, the traffic was close to 50% of what was predicted.

So clearly, there are some additional hidden variables here. They could be things like:

A.) Is there such a thing as position really? Do you get impression share every time?

B.) Does personalized search affect this?

C.) How much Google testing goes on in the SERPs?

D.) Is the AdWords data simply too high?

We can go on about each of these for hours, but I will comment on D here. One might speculate that Google has a big incentive to provide too-high estimates for AdWords. I know when I am preparing keywords for search campaigns, for instance, I use a cutoff of 1,000 impressions to decide what keywords are worth bothering with – other folks may use 500, or 2,000, etc. Think about this – is Google better off with ten auction participants on a high-volume keyword and one auction participant on a low-volume keyword, or are they better off encouraging people spend some of their budget on the lower-volume term, resulting in a mix of eight vs. three (i.e. a slightly less competitive high-volume auction but a MUCH more competitive low-volume auction). Google may have an incentive to overforecast simply for behavioral psychology reasons – so it could be that the AdWords Keyword Research Tool numbers are just plain high, on purpose (perhaps for this, or maybe some completely different rationale). This is an interesting area for potential research.

OK, Forget Everything – let’s just Calibrate it!

After thinking about this for a long time, I realized – all we need to do is calibrate the curve against the real world results. By cutting the numbers roughly in half again (actually, just dividing the numbers by about 1.75, until the curve predicted close to the correct amount), at least we have a curve that just about fits reality – for one website.

I updated the curve (see column 3 of Figure 1), re-applied it and got a great estimate, for each position grouping of keywords. As you can see, where one position is off, it’s made up for by others – differences sort of “come out in the wash”, as we hoped:

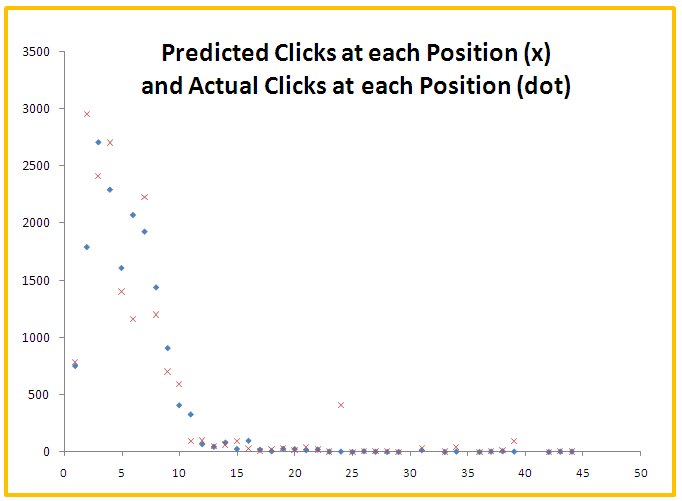

I also plotted the two curves, and although they are choppy, if you fit a power curve to each of them, they are right on top of each other with a very high R-squared value, so for estimating *overall* traffic potential, I think this is a pretty successful approach:

Now that we’ve “trained” our curve to be at the right level (calibrated really, but kind of like training), we need some “test” data reserved to check it against, to guard against “overfitting”. So I took data from another well-optimized website I have access to (only 75 keywords in this case), and applied the new curve to it. It predicted a grand total of 40 clicks – this website receives about 49 clicks a month – so I consider that a pretty successful test (an estimate that’s slightly low sounds like a good idea when coming up with these estimates anyway, better to underpromise and overdeliver).

How Does it Work for You?

I’ve attached a spreadsheet here, that can be used to estimate organic search opportunity for positions 1-50:

Organic Search Opportunity Calculator Spreadsheet

Try it on your own website data and please post the results below (i.e. how far off was it overall?). All you need are position and click data from Google Webmaster tools, and opportunity data from the Adwords Keyword Research tool – just use the spreadsheet to predict what traffic your existing terms *should* have, and then compare it to what they *do* have. Just make sure you use it only on non-branded keywords, for a website that’s already well-optimized.

If you want to try it on branded keywords, go ahead, but please report those results separately – maybe we can come up with a rule of thumb to apply to those if enough people try it out (i.e. multiply by two or something along those lines).

Just remember, individual keyword results will look crazy, but if you aggregate the keywords by position, the numbers should be within reason, and I’ll bet that the *overall* traffic is within 1/3 of actual traffic for most people. I wouldn’t recommend using this for any fewer than 50 keywords though, and the more the better.

Bonus

An easier task is figuring out how much incremental traffic you can gain from pushing terms up. For this we can use the original curve (or any of these curves, as the ratios of traffic at each position are the same).

There is a sheet in the workbook that allows you to do this as well. It only works for positions 1-20 – this methodology does not work well below position 20 (it results in crazy forecasts as you move up), but it can be really helpful in figuring out which keywords to focus on from a linking campaign perspective.

If you have pages ranking below position 20 for keywords, those pages may as well not exist as far as traffic is concerned anyway; you probably need to rework them, and maybe forecasting the opportunity as if they are new keywords/page combinations (i.e the other sheet) is a more appropriate approach.

Conclusion

Estimating Organic Search Opportunity is tricky business. What this exercise has taught me is – opportunity is much less than I had originally thought. This means strategies should be oriented towards creating *MUCH MORE CONTENT*, i.e. casting a net wider for more opportunities to rank for many many more keywords. I’m adjusting my recommendations to clients accordingly.

Great article! Thanks a lot! I really appreciate your effort.

Great stuff, Ted. Best analysis I’ve seen of CTR by ranking position. Thanks for the sample spreadsheet – will play with this a bit.

Thanks for the analysis and offering up the spreadsheet to go along with it. I particularly liked the way you accounted for conservative estimates by implementing constraints.

Very thorough job here. It’s kind of amazing to me that there isn’t more discussion about abandon rate. I guess it;s not something you really want to talk about with clients specifically but instead just incorporate it into estimated CTR. I think you’re about as spot on as you can be with this estimation process. You kind of follow the saying, “Under promise and over deliver” which I love. One thing with branded keywords, we have to keep an eye on the new Sitelinks in Google search. They’ve popped up in Google searches for keywords that may not necessarily be brand oriented but they match a domain so the results are pushed down because of it. This could change tho so it may not be something to really worry about.

When you first pinged me about this article, I knew it was going to be an awesome read that I would have to take some time with! Great post Ted!

Your section on whether clicks go to Paid or Organic search was really interesting. Whether Google provides accurate segmented data or not, we can never be sure. But I think the most we can take from the Google Keyword tool, is regardless of whether volume for a particular keyword mostly comes from Organic or Paid, we can still assume it to be a ‘searched’ term and work towards that.

I remember us discussing CTR for title tags and meta descriptions a while back on your meta description post…glad you touched on that!

Important note to all: I was having lunch with Dan Shure from http://www.evolvingseo.com and when I ran through this with him, I realized – the calibration was done against *broad match* data, not *exact match* data – so, to use the spreadsheet you need to use broad match data from Adwords. I’ve clarified in the posting and uploaded a spreadsheet with corrected instructions.

Something I’ve been thinking about for a long time. I will use this spreadsheet and report back. Thanks

Hey Ted,

Thanks for this very interesting article. I too have been finding that organic traffic has dropped for the top 3 positions. Now I’m a lot more conservative when estimating traffic for SEO clients. I’d prefer to look at exact match and take a lower 15% as estimated traffic. Anything more would be a bonus to my clients. Will check out the spreadsheet too. Cheers

Ted

Great job!

Been working through a few theories myself in an effort to better quantify SEO effort vs. reward.

Bottom line is that many SEO initiatives may not be short term wins based on cost of effort, but without qualifying the potential opportunity selling *anything* is a tough pitch.

At least having some basis around opportunity capture possibilities based on the ‘halo effect’ of well-implemented SEO gives better directional metrics on feasible ROI (and gives our sales guys something to propose and our teams some targets to measure against)

Cheers

Interesting BUT…

There’s one factor that should be taken in account and that’s the psychological aspect in all of this.

I DONT click on paid ads. Why? Because if ‘m searching for info I’m not going to the place where anybody with some money can shout it out. I think “correct me if I’m wrong” that if I look at my own behavior and most likely of everybody that left a comment here (professionals) will almost never click on the paid ads for that same reason. So for the B2B market I think the CTR for paid ads are very low even if they are the first 3 results.

As for the B2C market, I think it will go the same way like with telemarketing. People start to identify what is an add when searching and will leave them for what they are, Commercials! I think it was effective (if I would believe Google) when it was new, but at the end of the road it will be the same as all the advertising received at home, it will end up in the round file cabinet 😉

I even have comparising for my statement:

I have a website that ranks nr.1 for 3 keywords resulting in around 1000 unique visitors a month and growing. In a HIGH competive market (tablet pc’s), so there are always 3 paid results above me 😉

According to Google those 3 keywords would be good for arround 2500 searches (EXACT) a month. So that means that I’m getting about 40% off all search traffic since there are NO other marketing efforts for the domain (No paid, No Social, NO OFF PAGE SEO, NO nothing) I did al this exactly for 1 simple reason. To decide what every marketing effort is worth. I want to know exactly what the ROI will be for everything I do.

So, for a very competive keyword I harvest 40% for a number 1 position. That’s a little higher then Google wants me to believe 😉 cause they rather see me pay for that kind of result offcourse. But with Adwords I can never get those results and they would cost me a lot more than I’ve paid now 🙂

I think there can be also other reasons why CTR is dropping. Think about mobile searches, people search more on their mobile now a days. But when searching on a mobile you can be called (which it was made for) and therefor result in abandoned searches. And most likely you can think of a lot of other reasons due to an ever changing search experience. Youtube, shop results, and so on also show up in the search results.

But what I would like to know now…is if the amount is dropping down for only the “relative” percentages. I mean, the number of searches can be growing while the CTR % drop. Still that can mean that the number of click thru stays the same or even grows. And I use the same example of my website again. 3 months ago the number of searches a month were 2000 for those 3 keywords combined and now 2500, that’s an increase of 25% so even if the CTR would have gone down from 40% to let’s say 33% it would look something like this:

2000 * 40% = 800

2500 * 33% = 825

So even do the CTR drops, my vistor count went up with 3,125% 😉

As you can see, the numbers are up for interpretation and can be wrongly interpretated 🙁

I rther use facts (my own) than figures (from Google) 🙂

Ted,

This is fantastic work and I have started using your spreadsheet for my work. I’m wondering though, as Google gives less and less real estate to organic search terms, what kind of additional drop will we see in click through rates. I’m hoping very little but I feel like it will grow appreciably. Have you seen any change since you first wrote this article?

Cody,

Great thinking – I can take the sites I calibrated it with and re-look at their data and see if the estimate comes in above the actual now, and if so by how much (maybe like an annual calibration, or measurement of what you’re talking about). I think I put this out last September, so I will take a look in a few weeks, great idea!

This article I did on that topic is definitely up your alley, I did some back-of-the-envelope high-level guessing there:

https://coconutheadphones.com/introducting-the-controversial-theory-of-peak-seo/

I read one of the posts here commenting on the traffic estimates and whether people look at natural or paid results. I deal with the public on a daily basis and ask almost everyone. My best guess is 60-80% look at natural results.

Fantastic analysis… my one question is why broad match? Seems like you are jumping through a lot of hoops to try and make a dataset useful (broad match search volumes from the AdWords Keyword Tool) that is not held in high regard by many search marketers. Why not analyze the Keyword Tool predictions of phrase or exact match against your website actuals? I would think the match type with the strongest correlation would be the best one to model with…

Well, I’ll give two answers, my excuse, and the honest one.

1.) Since a page will always attract some long tail traffic along with traffic associated with the keyword it’s targeting, broad match makes more sense.

2.) When I did the analysis, I accidentally had Broad Match on and didn’t realize it until I was well into writing the article! Otherwise I probably would have picked Phrase Match actually for the calibration, I think it would probably be more accurate than a Broad-Match based one. Either way, as long as it’s calibrated, it’s better than the alternative (i.e. nothing).